Unpretentious spot with a gory history

Gary Kamiya

Published 8:33 pm, Friday, June 14, 2013

One of San One of San Francisco's more surreal historic sites is actually located a few yards beyond the city limits, near the southern end of Lake Merced in Daly City.

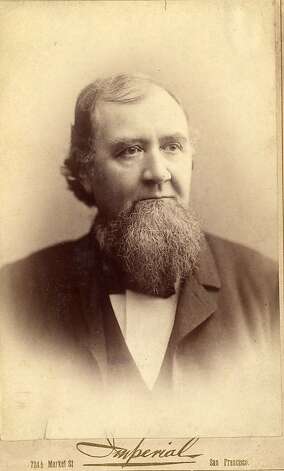

Down a little dead-end street, near an unexpected gated community and just beyond a forlorn picnic area, there's a small ravine. In this obscure spot, at 7 a.m. on Sept. 13, 1859, the chief justice of California, David Terry, shot and mortally wounded U.S. Sen. David Broderick in a duel.

Two old stone obelisks mark where the antagonists stood, terrifyingly close to each other - the site of one of California's most pointless tragedies.

The death - some called it murder - of David Broderick felt disturbingly preordained.

San Franciscans talked about the likelihood that he would be killed long before he actually was. Broderick himself was aware of his impending doom: Six months before Terry shot him, as he was leaving Washington to return to California, he told a friend, "I feel, my dear friend, I go home to die. I shall be challenged, I shall fight, and I shall be killed."

Yet, with an inevitability that recalls Greek tragedy, the 39-year-old senator did nothing to avert his doom.

Irish roots

Broderick was the kind of San Franciscan found throughout the city's political history. The son of a stonecutter, he grew up in the tough Irish neighborhoods of New York City, where he learned to play hardball Tammany Hall politics. Drawn by gold fever to San Francisco in 1849, shrewd and ambitious, he quickly became the city's political boss - mastering the arts of patronage and strong-arming.

By 1857, Broderick had maneuvered his way to a seat in the U.S. Senate, where he became an outspoken opponent of slavery.

Terry was also a classic San Francisco character, but of a type that did not endure.

In the city's early years, its "better classes" were dominated by Southerners, many of whom regarded New York Irish like Broderick as lower-class rabble and subscribed to a code of honor under which duels were an acceptable means of righting a personal wrong.

Terry himself was a veritable caricature of a proud, thin-skinned Southerner. The Texas native stood 6-foot-6 and weighed 250 pounds, and claimed to have killed a Mexican officer during the Texas Revolution with a bowie knife to the heart. The claim is dubious - Terry was 13 years old when Texas fought its war for independence - but his later career was filled with more than enough bloodshed to make up for that stretcher.

In one infamous incident, Terry stabbed a man in the neck, later shouting that it was outrageous that someone of his stature should be arrested "merely for sticking a knife into a damn little Yankee well-borer."

He came to California in 1849, established a law practice in Stockton and was elected to the state Supreme Court in 1855. Two years later, he became chief justice.

Promoting slavery

Terry was a member of the so-called "Chivalry Democrats," derisively called the "Chivs" by their opponents. As the country was convulsed by the issue of slavery, Terry and his fellow "Chivs" were determined that California would become a slave state.

That put Terry on a collision course with Broderick, and eventually he lashed out at the senator in a speech. Terry said his political enemies were "the followers of one man, the personal chattels of an individual whom they are ashamed of" - Broderick.

Broderick was breakfasting at the International Hotel in San Francisco when he read what Terry had said. Ashen with rage, Broderick shouted, "I have said that I consider Terry the only honest man on the Supreme bench, but I now take it all back!"

When Terry got wind of what the senator had said, he immediately challenged him to a duel. Broderick, who had had time to reflect, now decided that he was the target of a political plot, and declined the challenge on the grounds that he was engaged in an election campaign.

Persistent challenger

But Terry was determined to fight Broderick. As one historian put it, "For the next three months, Terry stalked Broderick as a hunter pursues a stag."

He announced his intention to challenge his enemy again as soon as the election ended. And Broderick, unwilling to "dishonor" himself, depressed and reportedly ill with pneumonia, acquiesced like a lamb going to the slaughter. When Terry challenged him again, he accepted.

Terry, Broderick, their seconds and 80 spectators met at a dairy farm near Lake Merced. The weapons were two Belgian pistols.

Terry had been practicing with the guns for two months. The distance was 10 paces. When the call "fire one" was given, Broderick raised his gun, but his shot went into the ground. At "fire two," Terry took careful aim and shot Broderick through the chest.

The senator collapsed and was carried to the Haskell House at Fort Mason, where he died three days later. (The house still stands at the foot of Franklin Street.)

The fatal encounter turned Broderick into a martyr and made a pariah of Terry. In an ending that also seems preordained, Terry himself was shot to death near Stockton by the bodyguard of a U.S. Supreme Court justice in 1889. Terry had been feuding with the justice, and a chance encounter in a train station led to a violent confrontation and Terry's demise.

Dueling out of favor

The San Francisco tragedy's only positive outcome was that it spelled the end of dueling in California. Broderick's death turned popular sentiment against the practice, and the Legislature eventually outlawed it.

Editor's note

Every corner in San Francisco has an astonishing story to tell. Every Saturday, Gary Kamiya's "Portals of the Past" will tell one of those lost stories, using a specific location to illuminate San Francisco's extraordinary history - from the days when giant mammoths wandered through what is now North Beach, to the Gold Rush delirium, the dot-com madness and beyond.

Trivia time

Last week's trivia question was: What animal-related incident factored heavily in the creation of Golden Gate Park?

Answer: Inhospitable sand dunes were the biggest obstacle to creating the park. When a horse's feedbag of barley spilled and quickly sprouted, workers realized they could use barley to stabilize the sand.

This week's trivia question: At the very end of the Beatles' last concert, on Aug. 29, 1966, at Candlestick Park, John Lennon teasingly played the opening bars of what song?

Gary Kamiya is a freelance writer and Bay Area native. His new book, "Cool Gray City of Love: 49 Views of San Francisco," will be published by Bloomsbury in August. E-mail:metro@sfchronicle.com